Until the rise of Roman supremacy, there had been a great variety of cultures and traditions in the colorful Mediterranean world. Each community had its own special physiognomy and also differed from the others in its cuisine and convivial habits.

As Rome’s power grew stronger, all of this changed rapidly. It was inevitable: from the end of the Republic onwards, the Eternal City had become a veritable melting pot of races, and in it men from all corners of the then known world met, attracted by its growing power and wealth.

In addition to this, in the Ancient Rome lived all those who, as slaves from far away countries, had become educators, pedagogues, cupbearers and cooks, pouring into daily life their habits, including food.

In the Ancient Rome, in short, all the cultures, habits, fashions and cuisines of the time met. The city absorbed all of them, but at the same time made a selection of them, having the last word, and thus imposing its own way of life in the rest of the Empire thanks to its influence.

It’s time for Rome Guides to lead you now to the discovery of the most curious personalities related to the world of good food in Ancient Rome, revealing their secrets and little obsessions.

The news about Roman food and banquets are many and numerous. They are provided to us by Latin writers, poets and historians starting from the authors of the Treaties of Agriculture, the oldest of which was written by Cato the Censor between the third and second century BC.

As well as giving a precise panorama of what was the agricultural and zootechnical production of the time, Cato also left us some excellent cooking recipes, of which he specified the exact ingredients, doses and cooking methods, so much so that they can still be cooked successfully today.

A few decades later, the poets were the ones to describe in every little detail the convivial life of their times, from simple dinners with a few friends to noisy and elegant private parties, to the sumptuous banquets offered by the Emperors. The refined Petronius, for example, dedicates an important part of his Satyricon to the rich and ridiculous banquet of the naive Trimalchio, who is introduced to you while he mocks the Emperor Nero and his court.

Juvenal, for his part, tells the story of the gigantic rumble, given (to tell the truth, a little unwillingly) by the lucky fisherman to the Emperor Domitian. The problem was that the fish was so big that there was no pot that could handle it, and this even led to an extraordinary session of the Senate, with Domitian forcing the imperial blacksmiths to make a custom-made pan for the turbot.

Latin literature, in fact, provides a veritable cascade of information. Pliny the Elder deals with the whole subject, from bread to fruit; Varrone describes all the zootechnical installations of the time, including those of the “piscinarii”, as at that time people called the owners of fish farms, who often became so affectionate to their fish that they poured all their love on them, as one would do with a dog or a cat; Hortensius, the great orator, was able to mourn the death of one of his moray eels for days; Antonia, Tiberius’ niece, had her favourite moray eel decorated with precious earrings, with the animal probably not liking the treatment.

Even historians give precise details about the diet of the ancient Romans and the preferences of the most famous people. In fact, we discover that the Emperor Hadrian was crazy about a curious dish, called “tetrafarmaco“, consisting of a wrapping of sweet dough in which were mixed pheasant, hare and wild boar meat. It was a very suitable food for a skilled hunter, as Hadrian certainly was.

Pliny the Elder, on the other hand, presents the Emperor Tiberius as a very frugal man, with simple tastes and a great appetite for cucumbers, so much so that his gardeners had invented glass-covered greenhouses mounted on wheels to take advantage of the sun as long as possible and make them available to him at any time of the year. Tiberius also loved carrots, which he had shipped directly from Germany, where he said the best ones grew.

Considering that he was almost a vegetarian, it is easy to explain his irritation when his son Drusus refused to eat the cabbage tops, which were served as a luxury dish on the austere imperial table.

Drusus had a dear friend with whom he spent several hours every day: his name was Apicius. Apicius was a famous and very rich gastronome, probably the most famous in the Ancient Rome, who ruined himself for his passion. We are talking about a man capable of preparing a ship to sail and ploughing the treacherous waters of the Mediterranean Sea to get some legendary shrimps, that the rumors defined as much bigger than normal; when he arrived in Libya, after having examined them and realized that the rumor was completely unfounded, since the shrimps were nothing special compared to those fished in Formia (not far from Rome), he turned the prow towards Italy again and went back without even touching the land.

As a consequence of all these follies, his heritage was reduced to a sum that, also if notable for someone else, was considered by Apicius to be absolutely inadequate to the standard of living to which he was accustomed. At this point, he preferred to offer his guests a memorable dinner and, after mixing his cup of wine with a powerful, fast-acting poison, he ended his life in the scenario that was most congenial to him, during a banquet on his tricliniar bed. Martial called this gesture “his most remarkable act of gluttony“.

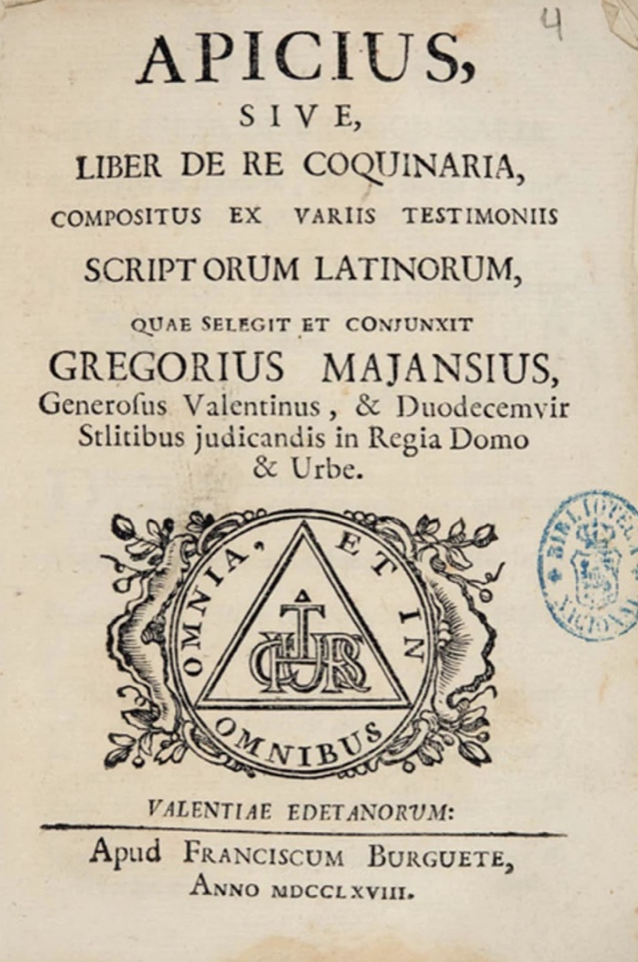

Apicius will become, over the centuries, a legendary character. Even today, there is a book of recipes that tradition has it that he wrote, but which is probably much later. In any case, regardless of what the truth is, this treatise on cooking, the “De re coquinaria“, contains numerous recipes that seem to have been carefully chosen from various different texts. This is the only treatise of its kind that has survived to the present day, and it is the only one we can rely on to get an idea of what the cuisine of Ancient Rome was like.

It is not an easy text to be interpreted, since it was directed specifically to professional cooks, who were entrusted with the preparation of meals at a time when there was certainly no lack of domestic staff. For this reason, the recipes are only quick notes and reminders for experts: they are lists of ingredients that are recommended to use, but whose doses are almost never specified.

One thing is certain: if the medieval monks, who saved a large part of Latin culture, felt the need to copy it, it means that it was really remarkable and certainly the best among the existing ones, so much so that it was still used for many centuries after the fall of the Roman Empire.