The following post is by Walker Lukens, my good friend who is now a contributing writer on Maiden Voyage. He is currently on a month-long trip in Africa. Read his last post here.

I wake up fully refreshed at 4:30 a.m. I don’t want to disturb my mom sleeping in the bed next to mine so I decide to go read on the porch. One step out and all the peaceful night time noises are now in my face, crawling down my legs and flying into my torso. I see twenty feet in front of me a large black mass turn it’s two-horned head toward me and snort. I stick my head in the door, tell my mom to come look but before she can make it over, the water buffalo runs off into the brush….

—–

8 a.m. Winding down the west side of the crater, all visible mountains are covered with green pasture. Maasai warriors are the only people in sight. The pastures are dotted with groups of their small huts—from far away they look like half-submerged balls of brown earth—surrounded by wooden wreaths. It’s tacky, I know, but I can’t stop myself from trying to sneak photos of them. Their robes, which I see now are intricately woven patterns similar to keffiyehs, and their black skin are gorgeous against the green and blue of the terrain. Muhammad can’t tell us why they wear red or blue except that they always have. The little children react to my camera and smiles by shouting phrases in English and waving. The adults look displeased, however, and Mohammad tells me they’re saying ‘pay me money for that’ in Kiswahili. Probably in a effort to stop me from taking photos and assuaged my curiosity, he suggests we go visit a village. We can pay a tribe $50 and they’ll give us a tour of their village and we can take all the pictures we want. I can’t figure out if this is some kind of special deal that he’s found, if there’s a particular village that does this, or if its going to be a sort of World’s Fair style exhibition.

We say yes and quickly find out that all Maasai villages do this. (We start to pass safari cars parked outside of many of them.) After leaving the mountain terrain, we pull into one of the villages. Mohammad exchanges a few words with the man who comes up to greet our car. Mom and I are uncomfortable at this point, not wanting to be spectators at an ancient and sacred ritual. Rough Guide to Tanzania says, “depending on your sensibilities, the experience can either be an enlightening and exciting glimpse into the ‘real’ Africa, or a rather disturbing and even depressing encounter with a people seemingly obliged to sell their culture in order to survive.” I only read this after. In the end it’s both.

A troop of Maasai men and woman walk out from the village twenty or thirty feet from our position. They’re divided by gender. The women are to our right and the men are about thirty feet to the left of the woman. Behind them unending sun-dried red dirt, the occasional acacia tree and further the barely-visible remainder of mountains. A boy, fourteen or fifteen years old, makes his way over to us. He introduces himself and explains that they are going to do a traditional welcome song and dance for us. Mom and I are at maximum discomfort level at this point but, once it begins, we see laughter, smiles, varying degrees of enthusiasm, eye rolling…. It’s clear that they’ve done this before and take it pretty lightly.

The male and female groups are each lead by one person. They begin a phrase and the group repeats. The male and female sections are not singing the same phrases. Rhythmically and melodically, they’re not in unison either (at least in any way akin to Western music.) The men sing rounds in low guttural tones. The women do the same in high shrill voices. The result is a sort of nebulous choir piece and the effect is hypnotic. (If I was a music journalist, I might call it cacophonous white spiritual.)

They finish and we’re led towards the village—two concentric circle fences with huts lining the outside one and a large tree at the center of the inner circle. Discomfort level is back up. We’re taken into the inner circle and told that we’ll hear another song. The singers, still divided by gender, are much closer to us now. Other, non-participating tribes men close us into the circle from behind. We’re in their home. We’re inside their private conversations and have no idea what they’re saying (is it us?) I feel their breath, smell their smell and hear their music. The same boy who took the money explains that they use the money to buy water and point to hundreds of plastic barrels. This song is even better than the last one—louder and more powerful since they’re closer. The men’s part is a shorter round and the vocal tone is closer to a growl. There’s still a leader but also someone jumping very high into the air at the end of each turn.

The second song from the Maasai

We go through the motions of being honored guests who deserve a welcoming song although neither host nor guest believes in it. In fact, we’re just paying customers at a poorly staged performance put on for non-native curiosos: no comfortable distance between spectator and performer, no seats, no beverages for sale and no playbill. Yet by failing to be a proper performance a more powerful and vertiginous outcome is achieved; two Americans in the middle of an alien ceremony, smack in the middle of a village and its people, in the middle of a country in the middle of a continent in a corner of the world that we poorly understand. The impulse is there to compare it, to tame it, to disconnect from it even, but for a moment there it’s just strange and frightening and beautiful.

Then, the feeling’s over. I’m coaxed into doing the jump with the men’s group. (This being the volunteer-from-the-audience portion of the magic show.) Discomfort spreading to cheeks and dripping down my back. No surprise: this white man can’t jump either (I had to, sorry.) The song finishes and we’re taken outside of the inner circle and deposited in front of several tables full of jewelry and crafts.

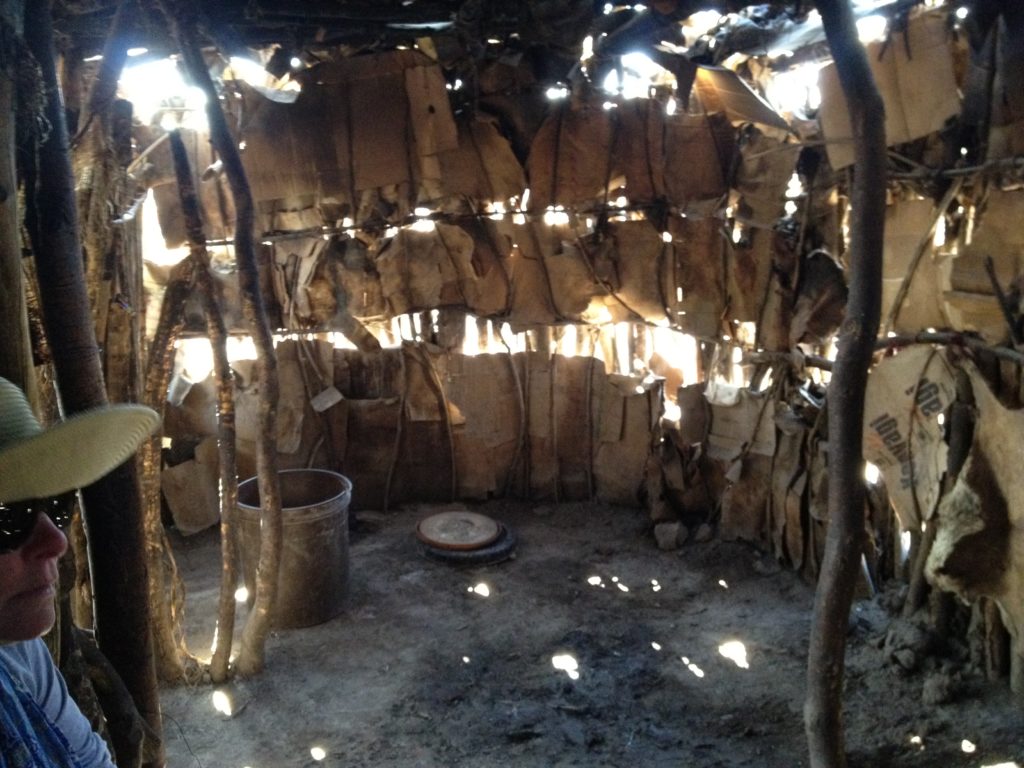

While all of it is well-made and unique, none of it is something I’m looking for. We both buy some stuff out of guilt. Then our guide leads us into one of the huts. It’s eight or nine foot in diameter and I can only half stand-up. The frame of the hut is built out of branches and the walls are made of newspaper, cardboard, mud and animal hair. We learn this is the home of one of the chief’s wives and her children. He has ten wives and he spends each night with a different one of them. This tribe will live here for two or three months before they move in search of fresh pasture for their cattle and rebuild their entire village. I ask what will become of this village and he shrugs and says another group will probably take it. We find out that the hut is also constructed using manure and human urine, which are great adherents apparently. My mom, while maintaining her cool, goes a little pale realizing we’re surrounded by this.

It all could have ended here but we’re lead out to a school house behind the village where a class of adorable little children, four or five years old maybe, demonstrates their ABCs for us in English. Our guide asks us for the money and asks if we can give it to him in small bills. Half the money will go directly to the chief, he says. Turns out the chief is also the kindergarten teacher and I see our guide hand over the money to him. (I still wonder where that other half went.) He tells me that an NGO gave them this chalkboard and the chalk a few years ago. Then, he asks me how ‘we’ learn at our home. (Is the question a standard part of the tour?) I say that its similar—it is the same methodology—but the differences, my privilege, are too much to articulate.

I ask the guide where he learned English and he tells me that he went to primary school fourteen kilometers away. That means he walked to and from school seven plus miles every day. It also means that at his age he’s probably done with his education. Most of the other boys in his age group have already left the village. They’ve gone to look for work and, as I’ve seen since, are all over Tanzania working as security guards, taxi drivers, porters, waiters—almost always they are wearing their traditional garb.

The Maasai have not benefited from the westernization of Tanzania. Still nomadic today, they used to roam all over the Serengeti, Ngorongoro, up into Kenya and down into central Tanzania. However, their territory has been reduced dramatically over the last 100 years. First, by the Germans and British who kicked them out of the Serengeti and Central Tanzania, and then by the Tanzanian government who limited them to the Ngorongoro Conservation Area only. How do you incentivize a nomadic tribe to opt into your economy? One way is to force them by taking away their water. There was a time when you could see them in Ngorongoro Crater but since the seventies they have no water rights to the lake there and their cattle cannot stay over night. Their herds of cattle ate tons of grass and reduced the amount of wild herds e.g. wildebeest and zebras, which in turn reduced the predator population and therefore safari-goers, money, etc. Now, the Maasai have to pay for water—and, indeed, ‘sell their culture in order to survive.’

I learn later that we could have haggled and gotten a lower price. I met some folks who proudly told me that they got the same treatment for $12. Did we see a $50 show? No, but we did glimpse contemporary Tanzania at perhaps its most incongruous angle. A tribe largely uninterested in ‘Tanzania,’ the sovereign state, working increasingly mobile and curious tourists on as favorable terms as they can. “… [This is]…the irrationality of the various statehoods imposed on Africa…that, for example makes ‘Kenyans’ out of one half of the Masai [sic] and ‘Tanzanians’ out of the other,” writes Shiva Naipaul about 1970’s Africa. This morning, we were witness to this irrationality or, perhaps, absurdity as it exists in 2012. The absurdity of having to simplify your culture into some ‘authentic’ form for tourists hunting after mementos, anecdotes, and perspective—the irrationality of thinking you can know someone else after an hour.

—-

1 p.m. A friend once told me that he loved returning to his hometown in West Texas because the sky is so big and the land so flat that he remembers how unimportant he is in the scheme of things. Driving into the eastern Serengeti gave me a similar feeling. The gravel road cutting through the unnervingly flat green plain. Deep blue sky stacked on top. The occasional outcroppings of rock and trees (without which we can’t mark our progress.) The big rainy season-sized clouds (without which we wouldn’t feel the shape of the sky). And, of course, the animals. Far away pairs of ostriches. Giraffe families. Zebras herds. Gazelles. I don’t feel unimportant so much as I feel like one fast, armored animal among many different kinds—as entitled to this place as they are. (For shame, that we forget that.) We’re zipping along in a big car, the windows are down, my mom says she feels like she’s water skiing and its awesome.

—–

3 p.m. I was told before leaving that you know you’ve got a good guide when every time he passes another safari car, they stop and exchange information. Through this method, Mohammad learns that there’s a leopard in a tree. He’s experienced enough not to tell us and to just take us there (what if the leopard leaves?) but we’re driving with more intention now. The terrains has changed. Taller grass, subtle hills, scattered trees. The roof is up and my mom and I are standing on the seats with binoculars around our necks. Other safari cars are also there. Leopards are nocturnal and this guy is trying to nap. This is one of the moments on the trip where I wish I had splurged on a nice camera. From a glance, you can only distinguish the leopard from the tree branch by his paw hanging down. A harder look reveals that his tail flicks ever so often. When he takes a deep breaths, his body does a lazy shudder. Then he looks at us, stands up on the branch—the top of his torso barely visible between the leaves—and extends himself upward so his legs are at their full length. Every muscle is fully flexed. His sharp teeth glare out of his wide open mouth. He looks at us again. Sit back down now with his head resting in the other direction. He was just stretching.

The car next to us is full of Americans and they have all of the hallmarks of a study abroad group. There’s one guy and many girls. Some have taken to dressing like the Tanzanians. Everyone is terribly sunburned. The conversations shifts between ‘the leopard they saw yesterday,’ goading the boy into getting out of the car (which is illegal by the way), ethnocentrism, and various anecdotes from earlier in their Tanzanian adventure. At one point, one of the girls asks the guide if they will see any honey badgers on this trip. The guide looks confused. Here they are looking at a leopard! One of the big five! One of the fiercest animals on earth! Why does she want to see a honey badger, he asks politely. She declines to explain. He says that they are hard to see in the tall grass. (Honey badger definitely don’t give a fuck about your African adventure, girl.)

—–

5:00 p.m. The terrain continues to evolve, the trees getting denser, the grass becoming shorter again, and the hills more pronounced. The stark blue sky and pale green plain from before have been replaced by many shades of green. At times, the bush is so dense the yellow grass is fully blocked for hundreds of feet. Our gaze moves up and down the hillsides for animals.

We see three female lions sleeping fifty yards from the road. While every one of their movements is imbued with significance for us in reality they’re just stretching like the leopard. For the first time we see baboon families occupying huge swaths of land. Some lope across the grass, others groom each other, some climbs trees, all are cute.

We come across a broken down safari car on the side of the road. The driver is Muhammad’s friend so he stops to help him. The family is milling about the car and the driver is putting on the spare. The man has a discreet Americanness about him: Cargo pants, corporate tee shirt over his paunch, goatee, wavy hair slicked back from sweat under his safari hat. Restless, he walks over to offer his guide some help. Then, he walks back to talk to his daughter. Then, he pokes his head in the car to check on his son. His hands rest on his hips then move to his pockets.

I’m tired of driving and feeling social so I go over and ask how long they’ve been here. He says not too long. Our guides must know each other I say and he agrees. His guide seems to know everybody he adds. I ask where they’re from and he tells me that he’s ‘out of D.C. And she’s out of New York.’ We’re roughly the same age, the girl and I. I ask which part and she tells me the East Village. I live in Williamsburg. We smile and make eye contact for a second. We live across a river from each other but we’re meeting here in this nondescript part of the Serengeti. My mind’s trying to work out the logistics of how we both got here at the same time and yet have never seen and probably never will see each other at home. The world doesn’t feel small to me. It feels helplessly big and complex. When so many of the most important things come down to timing how is this improbable meeting so meaningless? The moment’s not magical. It’s solipsistic. I can account for myself but everything else—a dumbfounding ‘how.’

We leave the feeling hanging there. We never exchange names.

About the author: Walker Lukens is a musician and ESL teacher who, most recently, was living in New York, NY. He loves traveling and has been all over the US, Canada, the Caribbean and Western Europe. He has also spent time in Brazil, Israel/Palestine and Serbia. Find him at WalkerLukens.com or on Facebook.

About the author: Walker Lukens is a musician and ESL teacher who, most recently, was living in New York, NY. He loves traveling and has been all over the US, Canada, the Caribbean and Western Europe. He has also spent time in Brazil, Israel/Palestine and Serbia. Find him at WalkerLukens.com or on Facebook.