The following post is by Walker Lukens, my student writing paper good friend who is now a contributing writer on Maiden Voyage. He is currently on a month-long trip in Africa.

My mom, travel companion and temporary Tanzanian resident, booked our safari through Antelope Safaris. Safari companies, and tourism in general, are big business in Tanzania. There are hundreds of different companies to choose from and tons of ways to get ripped off. You want to book with a company that has a TALA license and also with one that requires you to book well in advance (it means they’re busy). High season is during July and August, and there are price reductions for going during the March, April, May as this is the off season.

Safaris are tailor-made, all-inclusive packages, and range anywhere from a hundred to a few hundreds dollars a day per person. You can camp or you can stay in five-star hotels in the Serengeti. You can go for two days or two weeks. They plan everything from the moment you arrive until you leave: your flights or bus rides to and from, hotels, meals, guide, car. With the exception of alcohol and souvenirs, everything is paid for in advance.

I was initially pretty skeptical about hiring a company to plan our entire trip. Fancying myself a rugged independent traveler, package tours are not how I prefer to travel. But I quickly realized how impossible doing this would have been without a safari company, since 75% of the roads we traveled on were gravel, dirt or mud and riddled with holes. There were virtually no road signs and weak cell phone and radio signal. Not to mention, I can’t identify animals by their shit without a guide book nor can I spot a crouching lion in the brush while driving 40 mph or speak Kiswahili. While you could probably get to Ngorongoro Crater easily without a guide, a guide is totally essential if you want to go into the Serengeti proper.

——-

10 a.m. We meet our guide at the Mouth Kilimanjaro airport. Walking on the tarmac from the plane to the terminal. I see Kilimanjaro and Mount Meru in the distance, but these are other parts of the jet-lag montage unfolding since three this morning: drink instant coffee in the room, read book, check email, read book, take taxi, airport security, more instant coffee, ‘cheese croissant,’ walk to two-propeller plane, fly over water, fly over farms, etc. The open air terminal reveals all the operations of the airport. We’re shuttled into a room and then handed our bags through a cargo shoot that looks back onto the tarmac we just came from.

There’s an African man holding a sign that says ‘Suzan,’ a common misspelling of my mom’s name here. This is Muhammad. He’s our guide and we’re driving to Arusha, he says. This means nothing to us but we nod and head towards his beige Toyota Land Cruiser. Having only seen the variant I grew up going to and from soccer practice in, it’s funny to see an actual Land Cruiser—one meant to drive over any kind of terrain and not just suburbia. The car is massive: manual transmission, transfer box, two-way radio, 10 seats, built-in cooler, a ceiling that opens.

The first thing that strikes me about the road and its shoulder is that it’s the route for all kinds of traffic: cars, bikes, pedestrians, shepherds with herds of cattle and goats, farmers with carts of vegetables, stray chickens. Occasionally, we’ll pass someone dressed in vibrant red or blue robes. These are the Maasai, I’m told by my mom and Muhammad, and I will learn later that these are one of the most emblematic tribes of East Africa.

Tanzania was a British colony at the time cars came around, so we’re driving on the left side of the road and I’m sitting shotgun on the left side. I love driving and like the feeling of being on the left side even if I’m not actually at the wheel. Illusion of control! I’ve just realized that I’ll probably be sitting in car for most of the next 5 days. We settle quickly into what will become our in-car mode: little talking, no music, lots of looking out the window and drinking water.

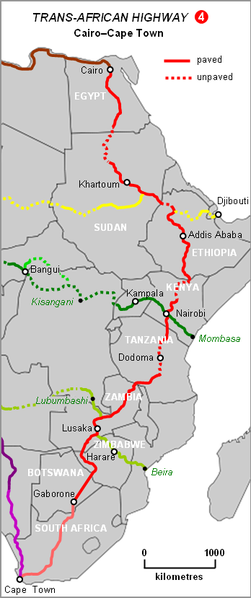

46 km (30 miles) and an hour and half later, Arusha feels like a bustling farmers market set in dirt, because from Road A23, that’s all it is. We go through a traffic circle, the intersection of our road A23 and A104. Mohammad tells us this is the midway point on the road that goes from Cape Town to Cairo. This seems remarkable to me, though I know so little about African geography.

Arusha is not the most logical mid-point geographically nor a particularly big city. I read later this is the Cairo-Cape Town Highway, or Pan African Highway. A still unrealized road first proposed by the British back when most of the countries it passes through were part of the British Empire (hence the Tanzanian detour.)

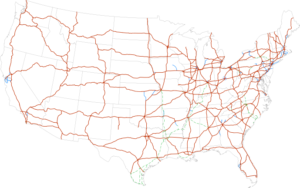

While the road does exist, there are several sections that do not have all-weather surfaces or are perilously dangerous. (Apparently, it’s impossible to pass from Egypt to Sudan by road and there are sections of the road in Kenya that are ‘plagued by armed bandits’, according to this article. ) The road is more than 6,000 miles long. To give you a little perspective, that’s like driving from Vancouver to San Diego to Miami to Boston and then to Chicago.

West of Arusha and out of Mount Meru’s shadow, the Africa I’d imagined opens up to us: the sun comes out, all the more brilliant with no mountain in the way, and the humidity decreases. The dirt is increasingly red. Roadside traffic continues and the number of Maasai increases. The age of these travelers range from young boys, most of who have herds of cattle with them, to teenage boys—some dressed in all black. Muhammed explains that these men in black have just been circumcised and must now spend two weeks sleeping outside their village in the bush. Now, I have no strong feeling about genital mutilation in Africa. I’m not apathetic, I just don’t think i’m capable of understanding it properly from my background. That being said, cutting off the end of a teenager’s —- and then sending him out into the bush to fend for himself seems exceedingly harsh. Manliness Merit Badge properly earned, gentlemen. No wonder they’re wearing black!

The apocryphal tale here is that a young Maasai warrior had to kill a lion during this two-week period.

——–

1 p.m. In front of us a low band of grey appears on the horizon. As the band of grey becomes a band of brown, Muhammad explains that this is the Rift Valley. We’re looking at a plateau. It’s completely filled up the horizon. My mom starts up about Dr. Leakey and Lucy and invokes the approval of my 6th grade world history teacher, Mrs. Webb. (Mrs Webb has come up often on this trip.) They found the oldest human and proto-human remains here, cradle of civilization.

The only town we pass between Urusha and Ngorongoro is Mto wa Mbu. From A23, the entire town appears to be trying to sell bananas and only bananas. Apparently, there are eighty plus varieties of bananas here. This town “…was declared a collective Ujamaa village as part of Tanzania’s ultimately disastrous experiment with ‘African Socialism,’ into which thousands of people were sometimes forcibly resettled from outlying rural areas,” says my guide book, The Rough Guide to Tanzania. What’s remarkable about Tanzanians is that this didn’t lead to ethnic strive or rebellion against the government. The town is incredibly diverse—the population is culled from 50 different tribes—but still rather small.

——-

While we only have a hundred or so miles to go from Arusha, we don’t make it the edge of Ngorongoro crater until 3:30. (The roads are paved but full of debris, potholes, random checkpoints, and reasons to stop.) It has been a long day in the car and I have been awake for twelve hours now. The climate is humid, a little cold, almost jungly. On the way up we see baboons. I’m contemplating a nap when we finally come to a clearing in the trees and get out of the car.

What’s below had no referent for me. About 12 miles across, the crater floor is an endless plain of brown and green. It’s bisected by streams or maybe rivers that all end in a lake whose entire surface reflects sunlight at this moment. “In all that vertiginous expanse, there was no sigh of human presence. Awesome emptiness. Awesome beauty,” Shiva Naipaul writes in North of South. I guess, at this point, that the lake is in the middle of the crater but it’s impossible to tell—a rainstorm obscures everything to the right of the lake from out vantage point. The storm, the entire sky to our right, rolls in over the lake. We see tiny herds of wildebeest make microadjustments to their positions and we hear nothing up here but our feet on dead leaves.

It’s a short time before we make it into the crater. Many herds of animals are visible at all times. We saw lion cubs playing while their mother pulled porcupine quills out of her side. A male lion sleeping by the side of the road. Two male hippos fighting so violently that one of them is forced from the pond, across the swamp, into another pond. Herds of wildebeest running in unison from our approaching car. We see two black rhinos (there are 25 left in the world) through binoculars milling about. Hyenas. Zebras. Warthogs. With the rain storm now gone, the rim of the crater can be seen twelve hundred feet up, completely unbroken around us.

After two hours, we leave for the lodge. I’m seventeen hours into my day and have been uncaffeinated since the airplane ride. I can hardly keep my eyes open. I lay down on the bed and fall promptly asleep. My mom tried to wake me for dinner and apparently I said, “It’s cool, mannnn, it’s cool.”

Animal pictures forthcoming once I figure out how to get them off my camera. These are all from my phone.

About the author: Walker Lukens is a musician and ESL teacher who, most recently, was living in New York, NY. He loves traveling and has been all over the US, Canada, the Caribbean and Western Europe. He has also spent time in Brazil, Israel/Palestine and Serbia. Find him at WalkerLukens.com or on Facebook.

About the author: Walker Lukens is a musician and ESL teacher who, most recently, was living in New York, NY. He loves traveling and has been all over the US, Canada, the Caribbean and Western Europe. He has also spent time in Brazil, Israel/Palestine and Serbia. Find him at WalkerLukens.com or on Facebook.